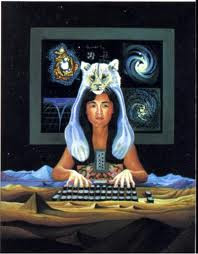

‘The cyborg is our ontology it gives us our politics’ (Haraway, D., 1991, p. 150)

In her Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway defines the cyborg as ‘a hybrid of machine and organism’ (p. 149); it is at once organic and engineered, the cyborg of fiction inhabits a world that is also organic and engineered. Haraway clearly argues that humans too inhabit such a world and that humans are equally organic and engineered. Haraway draws examples from science and medicine to persuade that humans have become cyborgs (p. 150). These examples are drawn from the westernised human and not humanity as a whole; in light of this I believe that it cannot be said that all humans have become cyborgs. Nevertheless, the cyborg of fiction, for Haraway, has become a part of our reality; it influences our reality; we take inspiration for our reality from the cyborg. The Cyborg of fiction, she says, maps our reality. The concept of cyborg for Haraway is genderless; ‘the cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world’ (p. 150). The cyborg is non-historical; it does not have a history that is conducive to the western tradition of an ‘origin story’ (p. 151). If we have become cyborgs then the relationship between human and nature in western humanist ontology (the belief that we have ‘unique capabilities and abilities’ (Audi, 1999, cited in Bennett and Royal, 2009, p. 397) becomes problematic; the way that the foundations of this system of dualism can be analysed has evolved or to be more precise it has changed. The boundaries between human and animal and organic and machine have been undermined as has the patriarchy that is the western tradition, which is widely viewed as being responsible for the exploitation of nature and the ‘other’. Within this framework Haraway suggests that the cyborg has brought the human closer to a pre-existing monism or affinity with nature. In deconstructing the cyborg we have the tools to deconstruct our ontology.